Dribble 2025

HEALTH KICK

Bernard Lazenbury

He was looking forward to the health spa’s evening “turn down” service and hopefully an expensive chocolate. Better than that Quinoa, Kale and Lentil rubbish on the menu. Entering his room after dinner he saw his favourite, Lindor, lying on his pillow. He groaned with disappointment. It was ‒ a radish!

WINNER’S COMMENT

Thank you Christine for the prize for winning the Dribble competition. It was nice to receive it especially as Lindor are my favourite chocolates. How did you know!

Write a Sonnet 2024

Winner

THE GOING DOWN OF THE SUN

Peter Davies

The clamour of the angry gods was hushed,

warm summer sun eclipsed the winter chill,

we laughed and teased, we bantered and we blushed

and as we fell in love the world stood still.

We wandered wild along the Peddars Way

as wondrous life for both of us began,

barefoot we strolled along a Gower bay

to linger long as only lovers can.

We stood and stared at Wren’s iconic dome,

we went to Flodden Field to curse and cry,

we scaled the walls where Romans dreamt of home,

and saw wide sunsets in the Suffolk sky.

Now ‒ as autumn yields to bleak November ‒

all alone I try not to remember.

Peter’s prize: a set of five CDs

Comment: Many thanks for the CDs received today. I am sure I will enjoy.

Runner-up

THE FISHING LAKE

Susannah White

The fishing lake is gleaming in the sun,

its ripple rings reflecting autumn trees.

A duck swims by and then another one,

crisp yellow leaves drift gently in the breeze.

The fisherman sits, flicking out his line,

dressed in a bobble hat and woollen top.

He throws some ground bait in from time to time

and when it lands, I hear a gentle plop.

Then suddenly he feels his line go tight

and, at the surface, there’s a flash of fin.

His rod bends sharply left then sharply right.

He grabs the landing net to bring it in.

Another mirror carp, the best all day.

He dips his net to let it swim away.

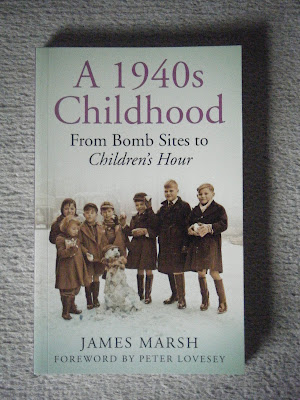

Susannah’s prize: Book

Open Article 2023

DECLINING WORLD

Roy Hewetson

Casting back to the massive changes in the United Kingdom of Great Britain following the ending of the Second World War, the then Government launched a ‘free’ universal national health service for all. They also began a countrywide drive to consolidate rented housing, managed by local councils for the benefit of the less well off plus those returning from military war service. There was nationalisation of dominant coal, road and rail conglomerates aimed to divert energy, bus, lorry and train profit to the community instead of lining the pockets of the few.

All was achieved with good intent, watered down over the years either by economic pressures or alternative political policies. Selfish greed played its part. Many rushed to extract short term gain at the cost of long term development. State enterprises saw profits eroded, resulting in losses many tax payers weren’t prepared to bear. Privatisation took hold. Water, sewage, telecom, mail undertakings were gobbled up by corporate bodies whose share ownership developed an international flavour. Many are now foreign possessions, some still benefiting from State handouts, removed from much of UK Government control.

Improvement to infrastructure such as pipes, rails, cables (many of which were out of date at takeover time in the 1940s) appears to have been slow, some argue secondary to the payment of dividends to shareholders of the international conglomerates. Hence the rash of burst pipes, shattered drains, gas emergencies.

The idea ‘Big is Beautiful’ has grown beyond the world of commerce. For decades those in National Government appear to have embarked on missions to further restrict local councils. A 1960s Royal Commission started a drift towards regional government across England. Achieving it in one blow was judged too great a political risk. The aim, some argue, is to gradually remove decision making from the many, to vest more power in the few. New mayors preside over larger authorities governed by ‘cabinets’ comprising a handful of local councillors. There’s comparatively little to do for the remaining elected representatives excluded from those cabinets or for the lowest tier councils. Small town and parish government inspires little interest, often making it difficult to fill seats to handle what the play areas, local halls and whatever other morsels are left to administer.

Introduction of drug prescription charges, dental and optical payments paved the way for rivals to compete with the NHS for work, creaming off those able to afford the ‘private’ fees. Rented Local Authority-controlled housing stock was reduced by encouraging tenants to buy at discounted prices, the dwellings left under councils’ control further reduced by creation of housing societies and associations. Students have to pay university fees.

From the mid-fifties onwards, the pendulum has been swinging from social control to private speculation. The postal and phone services were sold off in the belief ‘private enterprise’ was the way to benefit the country, but short term shareholder profit seems to come before their preservation, maintenance and improvement. In England and elsewhere in the rest of what survives of the United Kingdom there remain divisions between north and south, between the many who have little and the few who have more. Appreciation of the enormity of the swing from the revolution of the forties to the equally significant transformation in the decades that follow is perhaps to be left to future historians.

On the nation’s streets weeds continue to grow in gutters, pavements crumble, pot holes appear in roads. Some strive to suggest this is a temporary blip in the evolution of a nation. Others wonder if it’s evidence of the last throes of a dying civilisation? Will nature eventually have its way, gradually cloaking abandoned banks, pubs, palaces, roads and dwellings to leave future archaeologists in centuries to come to excavate the grass mounds, explore the forests in search of a civilisation as dead as those of the past such as Mayan, Aztec, Roman and many others.

PRIZE AND WINNER’S COMMENT

Whatever the Weather 2022

HOME FROM SCHOOL

Anne Brown

We dash through raindrops, past the church,

to turn by the Post Office, where we lurch

into the dry doorway, to watch torrents of rain.

Fork lightning stabs the sky as we run again.

The wind whisks us to the next shelter,

we laugh at thunder bolts and hasten on helter-skelter,

glad to stop at each safe spot,

a journey home – never to be forgot.

COMMENT: I love my surprise prize! So suited to the poem with all that rain. Anne Brown

I Can See Clearly Now 2021

SIGHT FOR SORE EYES

Alan Barker

“Ten pounds three pence,” the girl at the till pronounced, and promptly turned her attention

to her brightly-painted fingernails.

Dora pushed her glasses on to her head and fumbled around in her purse. “Here’s ten pounds but I’m clean out of thruppenny bits,” she said with a chuckle. “I bet you don’t remember those, do you, love?”

The girl glared at her and Dora’s friend, Nancy, said, “Here, I’ve got three pence, love.... Thruppenny bit indeed.”

“She’s a laugh a minute, that one,” Dora remarked as they left the shop. “Next thing we know she’ll be doing a turn at the Comedy Club.”

Nancy stopped and gazed across the road. “Goodness, was that a scream?”

Dora, who’d heard a noise but hadn’t attached any significance to it, turned also. A number of people were spilling out of the bank onto the pavement, a mixture of confusion and alarm on their faces.

“Where’s me glasses?” Dora said. “I can’t see a flipping thing without them.”

“They’re still on your head, you silly so-and-so.”

“Ah, so they are.... I still can’t see what’s happening. Give me a running commentary, would you, Nancy?”

Suddenly two men wearing masks ‒ at least Dora assumed they were men ‒ came racing out of the bank clutching large sacks and firing into the air. They scampered across the road, causing traffic to break sharply, and jumped into a waiting car which immediately leaped forward and slewed towards a side road.

“Write this down, before I forget,” Nancy said, as the vehicle negotiated the turn.

Dora fumbled around in her handbag and eventually found an old betting slip and a pencil. She carefully wrote down the car’s registration number as recited to her by Nancy and said, “How did you manage to read it so easily? It all seemed like gobbledegook to me.”

“That’s because you’ve had your glasses for donkey’s years,” Nancy replied. “You ought to invest in a pair of multifocals like mine; it’s like getting a new pair of eyes.”

“Yeah, as if I can afford them on my diddly squat pension. How did you manage to buy a pair?”

Nancy tapped her bird-like nose and said, “My darling kids clubbed together and got them for me for Christmas.”

*

The following day Dora’s phone rang and, without preamble, Nancy exclaimed, “You’re never going to believe this!”

Dora, who had been weeding her garden and was panting from the exertion of hurrying indoors, said irritably, “What’s the matter, Nancy?”

“That robbery we witnessed yesterday. The bank are offering five thousand pounds for information leading to the arrest of the criminals. Five thousand!”

“How do you know this? Is there something about it on the telly?”

“No, it’s in the local rag; I’ve got it right in front of me. Do you still have the registration number of the getaway vehicle?”

Her heart racing, Dora told Nancy to hang on while she fetched her handbag. “Got it!” she said, pulling out the old betting slip. “What do we have to do?”

Nancy explained the process and Dora said she would come over shortly. “Just think what we could do with all that money, Dora.”

“How about a holiday abroad? Italy or Greece maybe, or even the Bahamas?”

“We could also have a knees-up at the village hall, invite all our family and friends. Do you remember those parties we used to hold ‒ you, me and Nellie Bostock? Ah, those were the days. Do you know, I can hardly contain my excitement, Dora!”

*

Neither of them drove ‒ although Nancy had once held a provisional licence ‒ so visits to their local town were normally undertaken by bus. Dora could reach Nancy’s cottage by foot; this morning she found herself walking a little more briskly than usual.

Letting herself in through the back door ‒ she had her own key ‒ Dora marched into the sitting room saying, “What a wonderful day this is turning out to be!”

Nancy was sitting in her favourite armchair, a newspaper spread out on her lap.

“Where’s this article about the reward, Nancy? Let me have a butcher’s.”

Her friend seemed to be asleep. Dora shook her shoulder but still she didn’t respond. “Nancy, wake up, will you? Nancy!”

Dora stayed still for a minute, uncertain what to do. She couldn’t tell whether Nancy’s eyes behind her multifocal glasses were open or closed. Hesitantly Dora reached out and felt for a pulse. She didn’t find one.

“Oh no....” Dora put a hand to her chest and plonked herself down on the sofa. After a few minutes she picked up Nancy’s telephone and dialled 999 and, when asked which service she required, replied, “I don’t know. But my best friend has just died of a heart attack, which I don’t understand as there’s virtually nothing of her and... and I really don’t know what I’m going to do without her.” Her voice trailed away as she reached for a tissue. She was put through to an officer who explained the procedure and assured her that someone would be along to see to Nancy as soon as possible. After ending the call Dora went upstairs and found a freshly-ironed bed sheet in the airing cupboard. Back downstairs, she removed Nancy’s glasses and placed the bed sheet over her. On a whim, she took off her own glasses and replaced them with Nancy’s. She held up the newspaper she’d found on Nancy’s lap and realised she could read the writing clearly. She walked to the window and peered out, astonished that everything was so clearly in focus.

Dora stood still for some minutes, gazing out at the garden, until a tear rolled down her cheek and she brushed it away. Tucking Nancy’s glasses and newspaper into her own bag, she made herself a cup of tea and waited for someone to come.

*

Dora put her hand on the policewoman’s and said, “What did you say your name was, dear?”

“WPC Redbridge,” the officer replied, smiling.

“No, I got that bit. I meant your first name.”

“Lucy.”

It was two days after Nancy’s death and Dora was at the police station. “Ah, such a nice name. I knew a Lucy once. She was the daughter of the grocer, Mr Green. I used to call him The Greengrocer.” Dora snickered. “I always had trouble reading the labels on the jars and bottles, so Lucy went round the shop with me to find what I wanted.” Dora took off her multifocal glasses and made a show of cleaning them with a tissue. “I don’t have that trouble any more. Since I got these little beauties I can see crystal clear now.”

WPC Redbridge looked down at the sheet of paper before her and said, “Let’s go over your statement again, shall we? On the morning of 1 July you were walking along East Street on the opposite side of the road to the bank. You became aware of a commotion from the direction of the bank and saw various people coming out onto the street rather suddenly. Then you heard gunshots, and two masked men carrying sacks ran out of the bank and across the road into a waiting car which sped off down Avenue Road. You don’t know the type of car except that it was dark in colour, but you wrote down the registration number which is....” Lucy read out the number Dora had given her. “Is that all correct?”

“Spot on, Lucy.”

“Excellent. So all I need you to do now is sign this statement and we’ll take it from there.”

“And you’ve got my address and phone number, haven’t you?”

“Yes, I’ll be in touch as soon as I have some news.”

*

At the funeral it was standing room only. Dora and Nancy had been best friends since they were five years old. Yet, looking round the crematorium, Dora was astounded by the number of people she recognised and had forgotten about, those who appeared familiar but she couldn’t quite place, and others ‘I don’t know from Adam the Gardener’, as she put it to the elderly gentleman sitting next to her. That he fell into the last of these categories was inconsequential as far as Dora was concerned. Each time she spoke he had to lean towards her and cup his ear, so it was uncertain whether he grasped what she was saying anyway.

Presently the funeral procession came through, led by the officiant and the pallbearers carrying the coffin, and followed by the various family members ‒ more young than old ‒ walking in single file. The coffin was adorned with a floral tribute of yellow chrysanthemums displaying the words NANNY NANCY. Dora felt a tightness in her throat and squeezed her eyes shut.

*

“It must be fifty years,” Nellie Bostock said. “Shows our age, eh?”

“You speak for yourself,” Dora countered. “I was born on 29 February, so I’m only 18 if you want to be accurate about it.”

“And still behaving like it!”

They were all back at Nancy’s cottage and the two ladies were trying ‒ not very hard ‒ to keep their voices down.

Dora said, “D’you remember that time the three of us spent the evening at The Slug and Lettuce and on our way home we took a short cut across that fellow’s garden and Nancy ripped her skirt climbing the fence?”

“Will you stop it?” Nellie whispered, giving Dora a light punch on the arm.

“Care to share the joke you two?” It was Nancy’s cousin, Mary, her arms folded across her chest but a smile tugging at her lips.

“Just talking about old times,” Dora said. “I’m sure that’s what Nancy would have enjoyed if she was here.”

Mary nodded and said softly, “Shame her family decided to have the wake here. It’s not exactly no expense spared, is it?”

“Never mind, I’ve an idea.” Dora drew herself up. “Nancy said recently wouldn’t it be nice to have a knees-up in the village hall, like old times. So I was thinking perhaps that’s what we ought to do.”

“Nice idea,” Nellie said, “but who’s going to foot the bill?”

Dora winked. “I’ve some money coming to me.”

“What, through Nancy’s estate?”

“No. Another source actually.”

*

Dora fiddled with the handles of her bag as men and women dressed in black gowns and white collars pushed through the door to the courtroom as if it was their own living room. Presently WPC Lucy Redbridge appeared and Dora waved, relief flooding through her.

“Am I glad to see you, dear,” she said.

Lucy sat beside her and said, “There’s nothing to worry about, Dora. Once your name is called you’ll be taken through to the witness box and asked to repeat the oath. Then the barristers will ask you some questions about what happened on the day of the robbery and all you need to do is answer them clearly and concisely. Just stick to the truth and nothing can go wrong.”

Dora rubbed her forehead and said, “I lay awake all night thinking about that. The thing is, what I told you at the police station about the robbery wasn’t the full picture.”

Lucy gazed at her but said nothing, so Dora continued. “I was with a friend of mine, Nancy. She had her multifocal glasses on and read out the car registration number of the getaway car, which I wrote down. I couldn’t read hardly anything with my own glasses, so when I found Nancy had passed away the next day I tried her multifocals on and have been wearing them ever since.” Dora paused and added meekly, “Will I get into trouble?”

Lucy put a hand on hers. “Not as long as you tell the truth. I’m just glad you told me this before we went into court.”

“What about the reward? Will I not be entitled to anything as it was Nancy that saw the car registration number rather than me?”

“I don’t know, Dora. You may be due something but I should mention some other people took the number also, so they could be due a share of it. And we don’t yet know if the men charged will be found guilty. The important thing is to tell the exact truth when you go into the witness box.”

“Oh, well. Money doesn’t really matter when I think Nancy is no longer with us.” Dora fumbled about in her handbag looking for a tissue but only found the old betting slip with the car registration number written on it. “I suppose I ought to keep this?”

Lucy looked at it and said slowly, “Yes, you should. Especially as you backed the Derby winner and don’t seem to have collected your winnings. Did you not realise?”

Dora blinked. “But I backed Frankie Dettori on the favourite which finished plum last. I only ever back my little Frankie.”

“Not according to this, you didn’t. Look, this bet was £10 on Woodlands Gem which won at 50-1 if memory serves me right. So you should have £500 to pick up.”

Dora grinned. “I’d no idea. My old glasses were so bad I must have chosen the wrong number when I put the bet on. Since I’ve had the multifocals I only got the slip out to tell you the car registration number.”

Lucy gave her a look of weary affection as Nancy had many times. “But I think you should give those glasses back to your friend’s family. Who knows, you might be able to afford your own now.”

“I will do. But there’s something else I’d like to spend my winnings on.”

*

“You keep them, Dora,” Cousin Mary shouted. “You’ve paid for this little shindig so the least we can do is to let you have a pair of glasses which no one else wants. Besides, I’m sure Nancy would have insisted.”

They were at the village hall. The floor was packed with family and friends dancing to the sounds of The Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’.

“Thank you, Mary,” Dora said. “These glasses have made me see things in a different light. I can’t imagine being without them.”

“So what’s the upshot of the court hearing you had to attend?” Nellie Bostock asked. “Are you likely to get some of that reward the bank was offering?”

“I’ve no idea. Lucy ‒ the nice young police lady ‒ said it will take time to sort out. But I’m not worried about that. There are more important things in life, dear.” Dora paused, and smiled to herself. “Nancy may not be here in body but she’s here in spirit, all right. I can see her now, propping the bar up, gin and tonic in hand, egging us on to do a turn on the dance floor. She’s probably in rock’n’roll heaven right now.... ”